Note 5. World Literature

Aleksandra Zakharova

Translated by Julian Graffy

The problem of how to translate a literary text into the language of cinema became relevant as early as the 1900s, and probably most difficult of all was making film versions of foreign literature, working with “alien” material. Very often the libretti of films made from foreign books consist merely of retelling the plots of the artistic texts in question. With such an approach the effect is, as a rule, what Neia Zorkaia called ‘lowering’ (snizhenie; N.M. Zorkaia, Na rubezhe stoletii. U istokov massovogo iskusstva v Rossii 1900-1910 godov, Moscow, Nauka, 1976, pp. 99-110); the structure of the source is destroyed and simplified on screen.

In the libretti published here there is an attempt to expand the original plot with new material, which is intended in part to smooth out the ‘lowering’ effect. The search for this new material was simultaneously carried out in a number of directions.

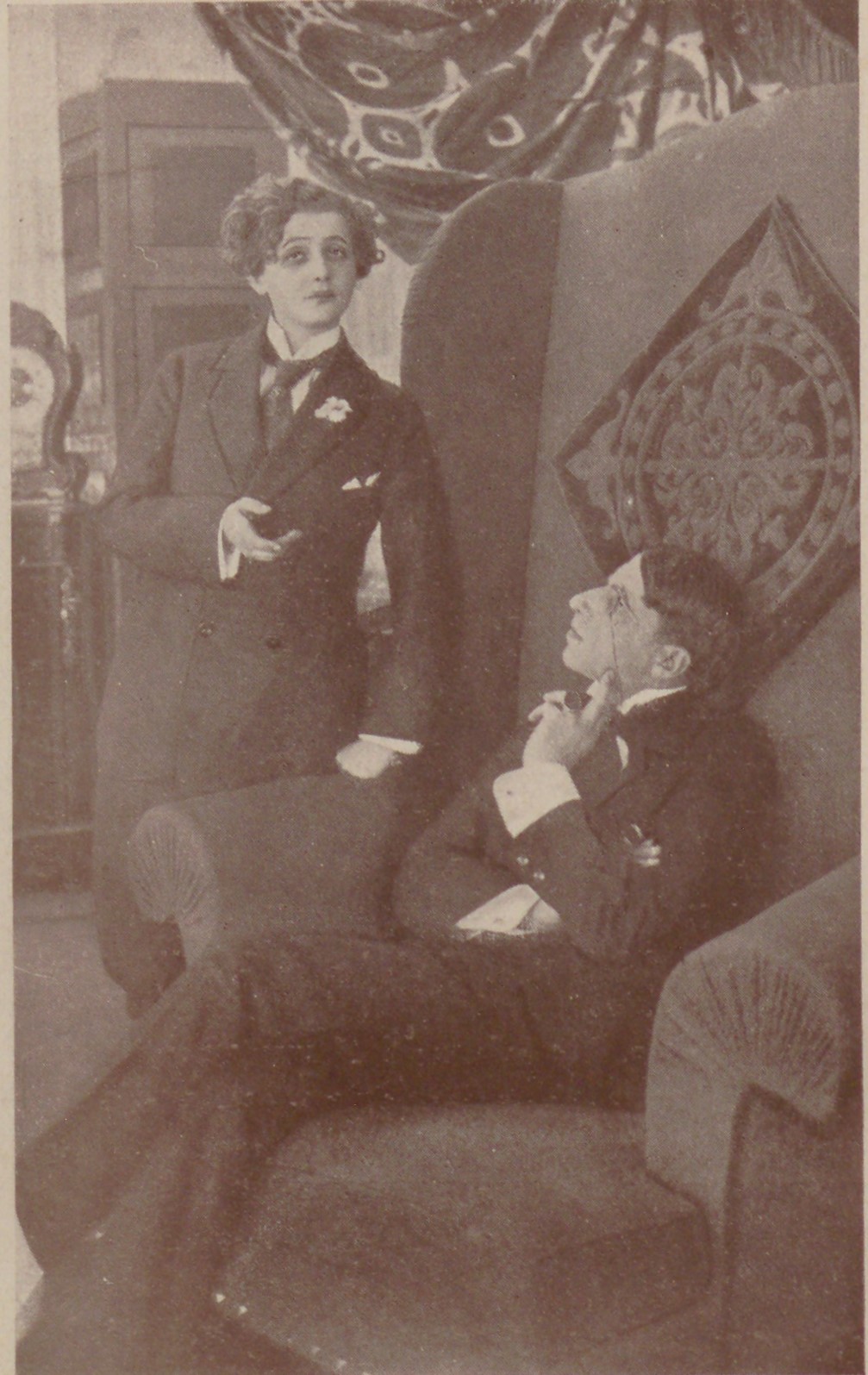

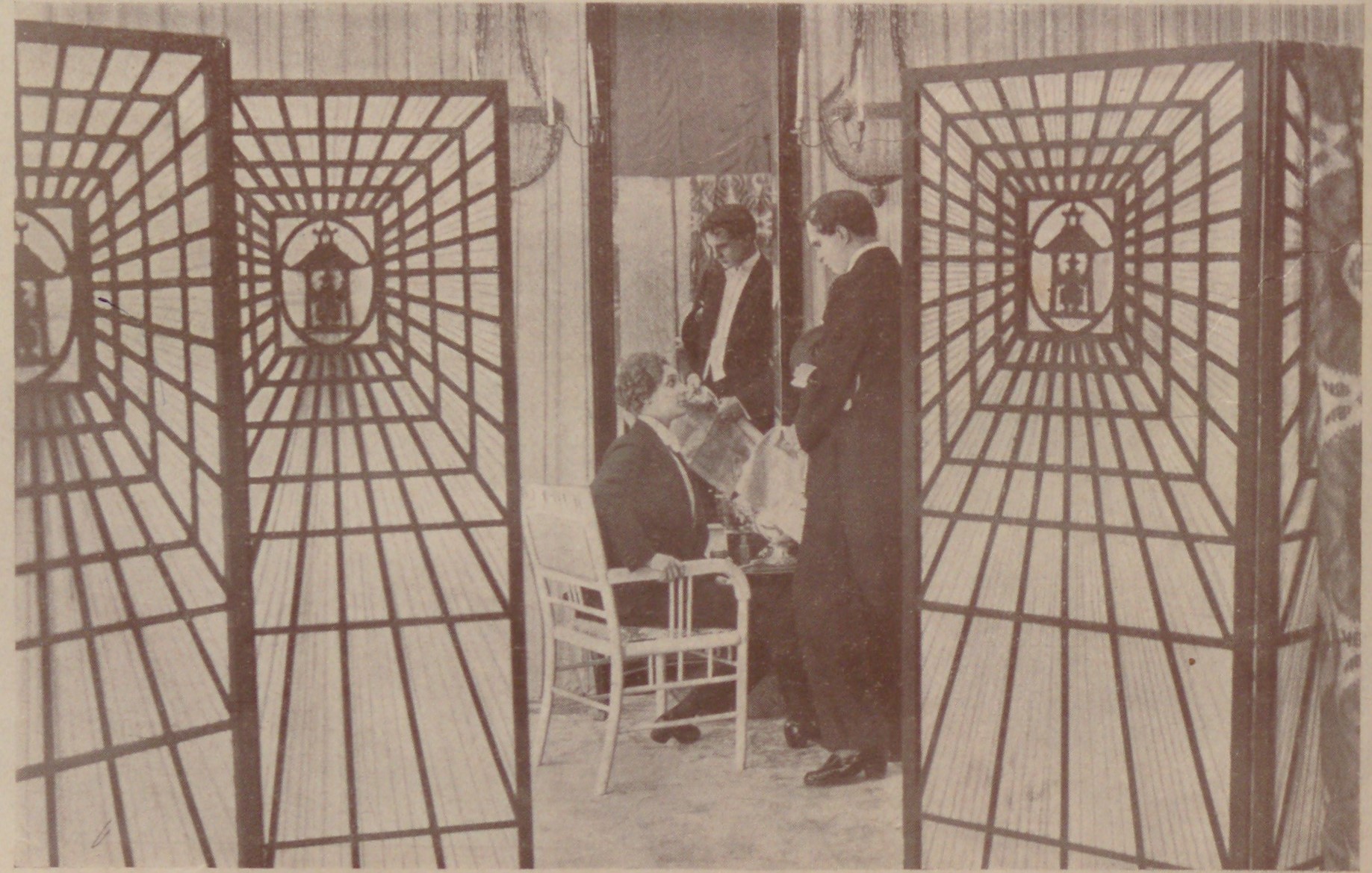

The Portrait of Dorian Gray (Portret Doriana Greiia, 1915): the biography of the author

The libretto of Vsevolod Meierkhol´d’s legendary film The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1915) begins, contrary to the source, with retrospection and the story of the protagonist’s parents and their unlucky love. Another notable feature is the reference to the biography of the author of the source text, which is an uncharacteristic device for early Russian film prose. In the libretto Wilde is associated with the hero of his novel, which connects with the idea formulated in the novel by Basil Hallward that ‘Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter’.

Libretto:

(A screen version of Oscar Wilde’s novel. From a screenplay, with the direction and with the participation of the director of the Imperial Aleksandrinskii Theatre Vsevolod Meierkhol´d.)

The name of Oscar Wilde belongs not only to literature and art – it also belongs to history, to the cultural history of humanity. The poet not only wrote talented verses and novels, he managed to make a poem out of his own life. This poem had a sad denouement, but this denouement was an atonement, which cleansed of all that was dirty and vulgar Oscar Wilde’s path to Golgotha, on which crucified beauty died.

The king of life – that is what his contemporaries called Wilde – moved among men like a Tsar, leaving them as an inheritance a code of beauty, a source of witty thoughts and vivid assessments. In the person of Oscar Wilde the “dandy” praised by Barbey d’Aurevilly, who told us the life story of George (Beau) Brummel, was perfected and reached its final form.

In his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray Wilde reveals to us the world of people who placed the ideal of beauty higher than all other idols before which humanity has bowed down. The poet showed us all the refinement, elegance, riches achieved by European culture, but his truthfulness as an artist did not permit him merely to sing a hymn of praise to this culture. He also showed the other side of the coin – the crimes, the filth, the hypocrisy and the vices of the priest of soulless beauty and his fateful end.

Dorian Gray was a member of London high society. He was a dandy in the full sense of the word. The grandson and sole heir of the wealthy Lord Kelso, he lost his mother early in life and his father even earlier. Lord Kelso’s daughter, Margaret, was a beautiful girl. One day she ran away from her father’s house without a penny in her pocket, after falling in love with a young officer of an infantry regiment. The officer was killed in a duel a few months after their wedding. It was alleged that Lord Kelso had incited some low adventurer to insult his son-in-law publicly. There was a duel and the officer was killed. The affair was hushed up but for some time Lord Kelso ate his cutlet at his club alone. He took his daughter back to live with him but it was said that she never spoke another word to him. Soon after this she died, leaving her son Dorian to be cared for by her father. Brought up without a mother’s tenderness, the youth received a brilliant education and imbibed all the elegant manners and all the refinement of the epoch. He appeared in high society in order to occupy one of the leading places in it. Dorian’s acquaintance with the artist Basil Hallward quickly turned into friendship. The artist grew to love the fine young man, who became an inspiration for his art. And the portrait which he began making of Dorian was not an ordinary work of his brush but something more. Dorian’s physical beauty and the chaste purity of his soul merged in the portrait into a single indissoluble symbol.

Alarmed by the thought of old age, young Dorian exclaimed:

I shall become old, revolting, terrible! But this picture will always remain young. Oh, if it could be the other way around! If I could remain eternally young but this portrait could age! For that I would give everything!

And this exclamation was like the formula of a vow. The portrait magically became a true likeness of Dorian’s conscience, while over many years beauty and youth did not desert this modern Faust…

Dorian found a new friend in the person of Lord Henry Wotton, a refined sceptic with a sharp wit and subtle taste. His speeches hypnotised the young man. A new world was revealed to Dorian. The paradoxes of Lord Henry became the canons of life for Dorian.

The fine young man decided to come to know all the enjoyments that the spring of life could give him. He fell hotly in love with the young actress Sibyl Vane whom he saw by chance on the stage of a small London theatre. The girl fell in love with “Prince Charming” – that is what she called Dorian. But happiness did not last long. She had known how to portray love beautifully when her heart did not know love.

When she became the captive of passion she lost the capacity to portray the beauty of love.

“What are you without your love? Nothing!” exclaimed Dorian and he abandoned the girl. She did not survive this and died that very evening.

This was Dorian’s first crime, his first sin – and the portrait faithfully recorded the damage to Dorian’s soul: a wrinkle of cruelty appeared on the portrait near the mouth. Dorian noticed the change and decided to hide the portrait in a special room upstairs, the key to which he always carried on his person. From then on, this room became for him a confessional to which he ran every time that he had committed some bad deed. And every time he found changes in the portrait.

Eighteen years passed in this way. Dorian remained as young and fine as at the dawn of his life.

Nobody knew the secret of his eternal youth but many were aware that Dorian was leading a bad life. And, one day, Dorian was visited by the artist Basil Hallward before his departure for Paris. He wanted at all costs to take a look at his creation, at the work into which he had put so much love and hard work.

Dorian agreed to show him his portrait, the portrait of the once pure and chaste Dorian.

“I shall show you my soul!”

And when the astonished artist saw all the horror of the moral and the hidden physical decay of Dorian Gray he was horrified. He tried in vain to persuade Dorian to turn to prayer, to correct his vice-filled life.

“It’s too late!” exclaimed Dorian. And a sharp hatred of the creator of this magic, fateful portrait flared up in his soul.

And he killed the artist.

With the help of an old acquaintance, an engineer to whom he was linked by some shameful secret, he destroyed the traces of his crime.

Nothing in his life changed, except that a bloody stain appeared on his hand in the portrait.

In an opium den, fate unexpectedly brought him face to face with the brother of the woman he had destroyed, Sybil Vane. But Dorian luckily escaped vengeance, deceiving the sailor with his youth. And it was only after he had disappeared that one of his victims who knew the secret of Dorian’s youth opened the sailor’s eyes. He started pursuing Dorian, aiming to kill him.

Good fortune rescued Dorian from his avenger with the chance killing of an unknown sailor who had hidden in bushes during a high society hunt. Dorian recognised the corpse as Jim Vane.

A meeting with a simple girl made Dorian uneasy. He did not ruin her, as he had ruined others. The hope flared up in his soul that pure, good feeling would heal the wounds of his sick conscience, would wash away the blood and the traces of his crimes from the portrait.

He went to London to look at the portrait.

“Hypocrisy too!” he sighed in despair upon seeing a new expression on his portrait.

And he decided to kill his conscience. But when he attacked the portrait with a knife a miracle took place. He killed not the portrait but himself. The young Dorian Gray shone with youth and purity in the portrait but next to it lay a dead, repulsive, ugly old man in whom with difficulty one could make out the earlier Dorian Gray.

‘Novye lenty (New pictures)’, Sine-Fono, 1915, 4, pp. 103, 108

Love’s Vain Surprises… (Liubvi siurprizy tshchetnye…): Russian realia and a change of genre

Love’s Vain Surprises… (1916) is a screen version of a Christmas novella by O Henry The Gift of the Magi (1906). Here the action is transposed from New York to Russia and, along with the alteration of the place in which the plot is played out, the genre of the work is also changed. A sentimental melodrama turns into a comedy, or, in the words of Veniamin Vishnevskii, into an ‘elegantly stylised “fairy tale” from last-century Russian life’, while O Henry’s heroes become the typical characters of Russian classical literature. Thus, the main protagonist acquires the profession of an official, which places him alongside the “little men” of Gogol´, Dostoevskii and Chekhov. His wife is given the name Liza, an important name for Russian literature, which makes the viewer recall the well known tale by Nikolai Karamzin. A touching story about a great love and self-sacrifice is reduced, in the Russian screen adaptation, to an anecdote about a ‘joke of fate’ against ‘little people’. This is probably why the basic event in O Henry’s work, the celebration of Christmas, is replaced in the libretto by the wedding anniversary of ‘poor folk’, since an interpretation of a biblical subject, which is what The Gift of the Magi is, is quite out of place in the afore-mentioned comedy of types plot.

Libretto:

Oh, what jokes fate sometimes plays on poor people!... The official Iliusha lived very happily with his wife Liza and their entire wealth consisted of his gold watch, which he had inherited from his grandfather and her ‘two plaits reaching down to the very ground like black snakes’… The dreams of little people are always little and Iliusha did not risk going far in his dreams: his cherished desire was a gold chain for the watch, while Liza dreamed of coloured combs for her luxuriant hair... And so, on the eve of their wedding anniversary, the young people conceived the idea of fulfilling each other’s desires… Without telling his wife Iliusha sold his watch and bought her some combs, while she sold her long plaits to the hairdresser and bought a gold chain… And when the following day they met and gave each other their presents, great was their sadness!... Love had played a bad joke on them!...

‘Novye lenty (New pictures)’, Sine-Fono, 1916, 8, p. 91

The Seventh Commandment (Sed´maia zapoved´): on Russian endings and the theme of religion

The source of the libretto of the film The Seventh Commandment (1915) lies in Guy de Maupassant’s novella Le Port (The Port, 1889), or in Lev Tolstoi’s ‘Françoise’ (‘Fransuaza, 1891), which is based upon motifs from Maupassant’s novella (as indicated by a mistake in Veniamin Vishnevskii’s filmography, where the source is called Maupassant’s ‘Françoise’). But here the plot is completely Russified. This is expressed not only in the transfer of the setting to Russia and the consequent changes to the names of the protagonists, but also in changes made to important details of the plot.

In the Russian version, as in the source, the central event is the encounter between a sailor and a prostitute who – as the characters realise only later – turns out to be his sister. In Maupassant’s version this fateful realisation leads to misery and hysteria, while in the Russian libretto things are sadder still: the hero kills himself and the heroine goes mad. Clearly this reflects the tendency noted by Iurii Tsivian for ‘Russian endings’ (Iu. G. Tsiv´ian, ‘Neskol´ko predvaritel´nykh zamechanii po povodu russkogo kino’, in Velikii kinemo. Katalog sokhranivshikhsia igrovykh fil´mov Rossii 1908-191, Moscow, NLO, 2002, pp. 8-9): pre-Revolutionary cinema was drawn to tragedy.

The idea of the work is also slightly adapted for Russian viewers: the moral announced by Tolstoi, ‘All of them are someone’s sisters’, is broadened and Petr’s mistake is represented as a breach of the Seventh Commandment (‘Though shalt not commit adultery’).

Thus, in the libretto the gospel theme announced in the title of the film is given greater prominence.

Libretto:

It is not the story of a fall, not ‘a black tale of white slaves’ that will engage you in this picture… No! You will shudder from the horror of the abyss into which the human soul can sometimes fall as the result of a fateful combination of circumstances… Chance creates an absurd, unnecessary and at the same time terrible tragic element in life… And this is the story which is told in this picture.

Mariia Bubnova, a beautiful young woman who had been left with no means of subsistence after her parents’ death, got a job in an atelier making ladies’ dresses. The modest and undemanding girl worked as hard as she could. But fate then ordained that Mariia was noticed by the human trafficker Madam Kluk, who was taken by the pretty girl. And so from that moment Mariia’s fate was decided. For the good salary offered by Madam Kluk Mariia began to work for her as a domestic tailor. But… ‘they did not sew much there and the strength there was not in the sewing…’ The first unconscious step had been taken… Gradually an abyss began to open in front of Mariia’s feet and it was ready to swallow her up at any minute. Baron Miller, who was an habitué of Madam Kluk’s house, made every effort to possess the girl. One day, after persuading Mariia to have a cup of coffee with a group of friends, Kluk slipped an intoxicating anaesthetic into her drink and Mariia became the victim of a cruel and shady enterprise. There was no way back!... Once she had stepped on to the slippery slope, Mariia began to slide down its smooth incline… The binges began, the ‘mad nights, sleepless nights…’ and in the end we see Mariia on the street… The art of love has turned into a filthy trade. One evening, caught in a police raid, Mariia found herself in a police station, from which she returned with the ‘yellow ticket’ of a prostitute…

The joyless, bitter life of ‘one of the many’ brings Mariia into contact with a pimp who tortures and exploits her, sending her out ‘to work’… Later we see Mariia in a brothel. And it is then that the horrifying drama which was the basic idea of the piece is played out. Mariia’s brother, the sailor Petr, after long years of wandering, returns about that time to his homeland. Having received permission from the authorities to see his relatives, he is horrified to learn sad news in his home town: his father has died and there is no address for his sister. Seeking oblivion, Petr goes to a pub and here, in the noisy company, in the intoxication of a drinking bout, he drowns his sorrows. It is in this pub that he meets Mariia. Merciless fate completes its vile deed – it throws brother and sister into each other’s embrace… In the morning, when paying Mariia, Petr realises from a few chance words she utters that he is in the presence of his sister. His horror is indescribable.

Everything becomes a blur for him… The Seventh Commandment has been broken!... Realising that after that further existence would be continuous torment, Petr kills himself. Stunned by what has happened, Mariia loses her mind. Thus it was ordained by the implacable hand of Life on the pages of the Book of the Fates…

‘Novye lenty (New pictures)’, Kine-zhurnal, 1915, 15-16, p. 137

Have you spotted a typo?

Highlight it, click Ctrl+Enter and send us a message. Thank you for your help!

To be used only for spelling or punctuation mistakes.