On Parody

Nadezhda Shumlevich

Translated by Julian Graffy

In the article ‘On parody’ (1929) Iurii Tynianov sums up his search for a universal definition of parody, which he had begun in ‘Dostoevskii and Gogol´ (Towards a

Theory of Parody’ (1921). Here Tynianov also fills out the conception of the history of literature in general which he had articulated earlier:

The evolution of literature and in particular of poetry is accomplished not only by means of the invention of new forms, but also, and in the main, by the application of old forms in a new function. And here we might say that both imitation and parody play their educational, experimental role (Iu.N. Tynianov, ‘O parodii’, in his Poetika. Istoriia literatury. Kino, Moscow, 1977, p. 292).

If we apply this theory to early cinema, it turns out that pre-Revolutionary cinema plays the role of the “new”, in relation to which more established forms of art, literature and theatre, will function as the “old”.

“Lili Fleri” podvel

The film Let Down by “Lilie Fleurie” (“Lili Fleri” podvel, 1914) travesties the Shakespearean Othello plot, transporting it into the comic plane. Possessed by “devilish jealousy”, Rulanov finds the scented handkerchief of his wife, who had decided to learn to dance the tango and to perform it as a birthday surprise for him, but the whole plan was thwarted by the “perfidious smell of her favourite perfume”.

Libretto:

An atmospheric picture. For it examines the fashion for introducing something as vexatious as the tango… And how much it damaged Rulanov’s blood, how much it might have ruined his health… This is how it was. His wife wanted to please him… don’t smile… just the tango for his birthday, and, of course, she wanted to do it as a surprise… but this was where Rulanov’s devilish jealousy got mixed up in it and the perfidious smell of his wife’s favourite perfume… after having run around ninety seven Ivanovs (all of them tango teachers and manicurists) with the scented handkerchief, Rulanov finally found the “perfidious Desdemona” and… started to learn the tango. It’s good that it turned out that way because when he is angry Rulanov is terrifying and he might have killed her and… who knows what else he might have done…

‘Novye lenty (New pictures)’, Sine-Fono, 1914, No. 12, p. 66

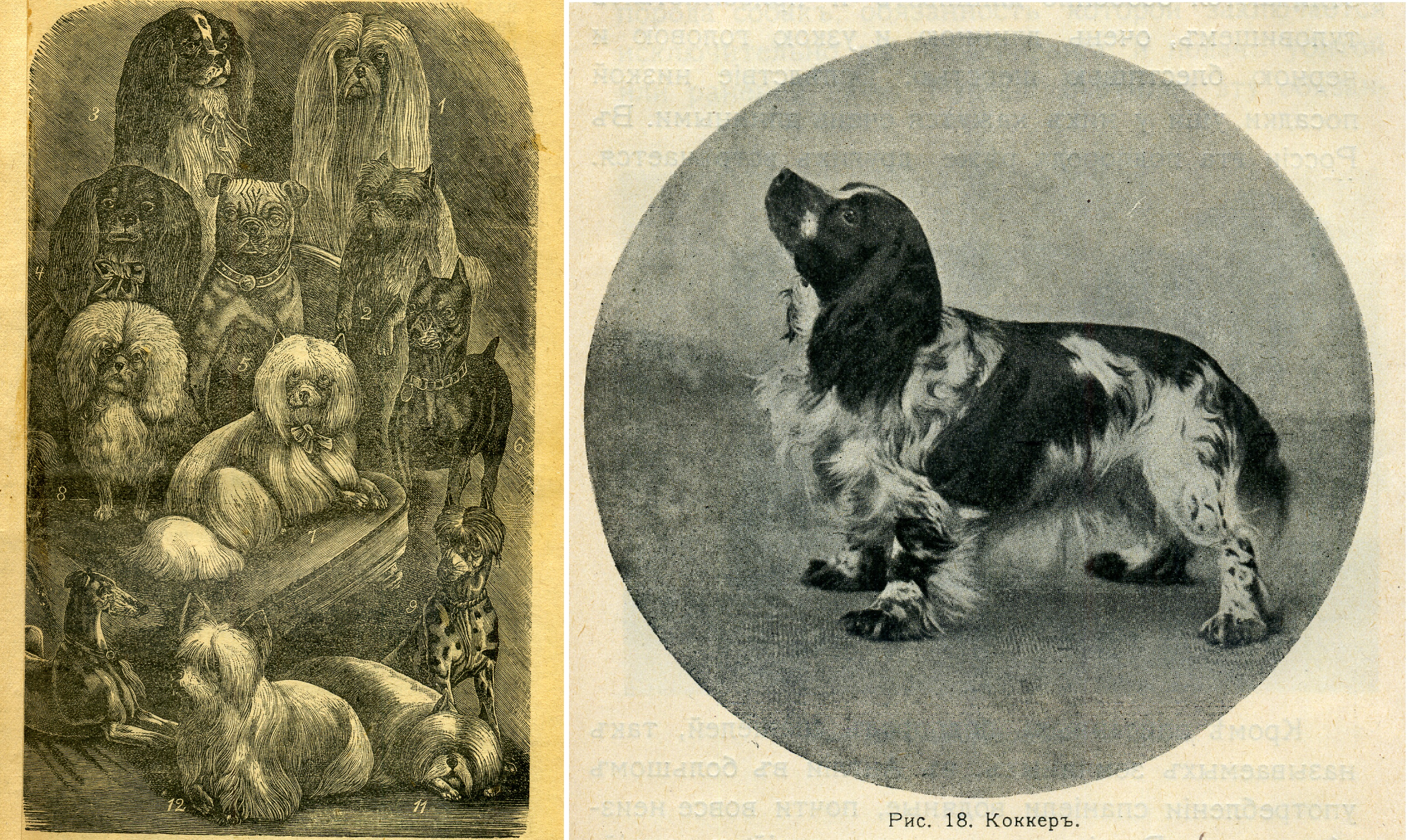

And We, Like People (I my kak liudi)

The singularity of this film lies in the fact that the roles in it are played by the animal actors of Vladimir Durov’s Theatre and that he himself is the author of the script. The principle aim was to portray a “hackneyed human drama”: the parody develops through its focus on a specific genre. Ivan Miatlev’s well known poem ‘Roses’ (‘Rozy’, 1834) served as a “maquette” for the film and we can note “plot” similarities with the base poetic text: the motifs of the fragility of love, of death and of the cemetery. In his substantial work The Training of Animals (Dressirovka zhivotnykh), Durov recalls and describes in detail how he achieved naturalness in his experimental actors “playing their feelings like the strings of a guitar” (V.L. Durov, Dressirovka zhivotnykh. Psikhologicheskie nabliudeniia nad zhivotnymi, dressirovannymi po moemu metodu (40-letnii opyt). Novoe v zoopsikhologii, Moscow, 1924, p. 124).

A critic writing in the journal Proektor treated the unusual material with a great deal of wit. It may seem that he is discussing the performance of the “acting snouts” completely seriously and the review itself appears a little parodic:

Pik’s acting is matchless, especially the expression of his ears and eyes. He has performed his role of the tender and devoted young lover with youthful fire. […] And we must also note the talented acting of John Bulldog (as the valet) and of Mok Mokovich Terter´erov (the postman). Tuzik (the Lord’s lackey) displayed brilliant abilities in his minor role. He will definitely go far (‘Kriticheskoe obozrenie’ (Critical Survey), Proektor, 1915, No. 3, p. 13)

Libretto:

(The story of a canine attraction in four parts, with the participation exclusively of four-legged and winged actors. The main acting snouts: Pik Pikovich Fokster´erov, a society dandy. Mimi, his beloved. Lord Serbernarov, a gouty old man, Mimi’s guardian.)

Pik’s life passed without a care. As a society dandy he enjoyed life’s benefits without a care until an unexpected meeting with Mimi radically altered his outlook. What had begun as a harmless society flirtation and a light-hearted courtship of Mimi was gradually replaced in Pik’s heart by a deep love. Pik realised that he loved Mimi, loved her more strongly and passionately than he had ever loved anyone else. The timid and tender Mimi responded to her heart’s chosen one with as profound reciprocal feeling. It seemed that nothing could impede the happiness of the loving couple, but Lord Serbernarov, Mimi’s guardian, had a completely different attitude to the matter. After intercepting a letter from Pik to Mimi he went to Pik’s flat, where he found the lovers. After a stormy scene in which he required Pik to explain himself, he found Mimi, hiding from her threatening guardian. Lord Serbernarov kept a sharp eye on his ward, who was securely locked behind seven locks in Serbernarov’s house. But knowing Pik’s persistence and tenacity, he did not trust the reliability and strength of the locks. And so Serbernarov nurtured a secret plan to take his ward far, far away from her beloved. Preparations for the journey were swiftly concluded. “Mimi, we’re going away.” Poor Mimi’s resistance was all in vain, the will of her guardian was unbending. Seeing that it was pointless to struggle against Serbernarov, she decided to employ cunning and at the very last moment, as they were at the station and about to leave, she contrived to send Pik a note. “My guardian is taking me to the Canine Riviera, to the resort of Woof-Woof. Farewell. Your Mimi.” When he got Mimi’s letter, Pik rushed to the station. Having missed the train that was taking Mimi to the Canine Riviera, he rushed off in pursuit. Misfortune pursued him and after many an ordeal he reached the port from which a steamer was to take Mimi to the resort. Here the last blow fell on poor Pik – the steamer had departed, taking with it the aim and the joy of his life: Mimi had departed. Pik’s poor heart could not withstand this final blow and the unhappy creature ended his life by throwing himself into the cold watery abyss

‘Novye lenty (New pictures)’, Sine-Fono, 1915, No. 4, p. 117

Popalas´ and Spasenie blizhnego

The farces She Was Caught Out (Popalas´, 1915) and Saving Your Neighbour (Spasenie blizhnego, 1916) play upon the widespread image of the “artiste from the café chantant” as a femme fatale, a “wicked demonic temptress”. In the first case the comic effect arises from the failure of the “cunning ploy” of the calculating femme fatale.

Libretto:

She Was Caught Out (Popalas´). The “Black Earth Region Landowner” Fedul Shishechkin gets a telegram from a notary in town demanding that he come immediately to sign some important papers. Much against his will, Shishechkin leaves his wife and children. He has to earn some money, especially for the future heir whom the Shishechkins are awaiting so impatiently. And that it will be a male heir there is no doubt… the nanny’s omens will not let them down… And seen off with admonishments, instructions and so on, Shishechkin leaves for town. In town he meets the notary Gvozdikov, well known for his fast living and idling but an extremely fine fellow. Gvozdikov has set himself the aim of seducing the virtuous Fedul away from the true path, with which aim he takes him to a café chantant. A wicked devil-temptress in the shape of an adorable chantant artiste makes an irresistible impression on Shishechkin. He gradually begins to forget tasty buns and fresh jam, he remains in town longer than his business requires, and he does not even return for his wife’s name day, limiting himself to congratulating her by telegram. But the artiste is dissatisfied – so far Shishechkin has not given her a single present, and she complains about his stinginess to Gvozdikov. “Tomorrow Fedul will get his money”, Gvozdikov tells her. As a woman with a head for business, our artiste decides to play a cunning trick. She gives her necklace, which is worth fifteen thousand, to a jeweller of her acquaintance, telling him to display it in his window and if a buyer turns up to sell it to him for six thousand… She promises the jeweller a thousand roubles as commission. In this way she will receive from her “trick” with Shishechkin “five thousand and I get to keep the necklace”. The trick is cunning and artful, but… fate arranges things completely differently. Initially everything went swimmingly… Softened up by the artiste’s wiles, Fedul buys the necklace which Korobochkina has pointed out to him and the next day Korobochkina receives her five thousand from the jeweller and waits for Fedul to turn up with his present. But meanwhile Fedul receives a telegram informing him of the birth of his male heir. In his delight he decides to go immediately to his village and judges absolutely correctly that it is better to give the necklace to his wife than to some artiste whom he is scarcely likely ever to see again… You can imagine Korobochkina’s indignation when having waited a whole day in vain for her landowner, she went to see him in his hotel and learned that he had left… the business deal had turned out disadvantageously for her, since she had to take exactly a third of the value of the necklace…

‘Novye lenty (New pictures)’, Sine-Fono, 1915, No. 21-22, p. 74

In the second film the conflict also takes on a tragic tone: the “salvation” by his strict parents from “the claws of vice” of a son who is in love with a singer is effected by means of trickery. We have before us the same plot collision as in And We, Like People: the prospect of an unequal marriage between two lovers is forcibly destroyed by their elders and leads to their parting. Returning to Tynianov’s article, we recall that parody by no means promises something comic.

Libretto:

Save Your Neighbour (Spasenie blizhnego). Zhorzhik, the only son of the Voinitskiis, fell in love with the singer Ania Frank. When his father, an old moralist, learned about his son’s passion, he decided to use any means available to him to extract his son from “the jaws of vice”. But this is not so easy. “Zhorzhik” loves his Ania, trusts her and remains unmoved both by the exhortations of his parents and by the flirtatious behaviour of his cousin, who is in love with him. A friend of the family, a lawyer, is called in to help, but once he makes Ania’s acquaintance he starts to pay court to her himself. Finally, Zhorzhik’s stepmother, who has also been intensely involved in “saving her neighbour”, resorts to treachery. By bribing Ania’s maid she persuades her to secrete Zhorzhik’s cufflinks in Ania’s chest of drawers and then she goes round to her house and accuses her of theft. The lawyer, for his part, entices Zhorzhik into giving him Ania’s letters and photographs and returns them to her in Zhorzhik’s name. The young couple cannot survive this assault. Zhorzhik finally decides to pay favourable attention to his cousin, while Ania is left with no option but to accept the proposal of the lawyer who is in love with her. By fair means and foul the neighbour is saved.

‘Novye lenty (New pictures)’, Sine-Fono, 1916, No. 1, p. 151

Have you spotted a typo?

Highlight it, click Ctrl+Enter and send us a message. Thank you for your help!

To be used only for spelling or punctuation mistakes.