Note 3. War Comedies

Aleksandr Anisimov

Translated by Julian Graffy

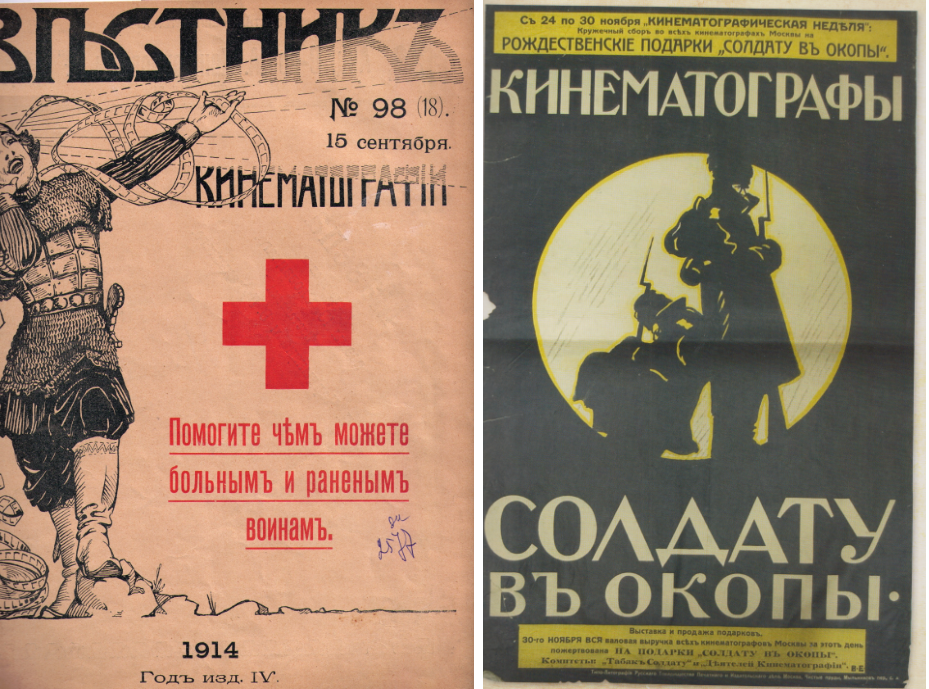

With the start of the First World War films on military themes naturally became especially popular. And although the majority of this group of films were dramas, comedies were also made, as well as films intended, above all, to maintain soldiers’ morale.

One of the first such films was Christmas in the Trenches (Rozhdestvo v okopakh, 1914), directed by Iakov Protazanov and released in the Russian Golden Series. According to Veniamin Vishnevskii’s filmography, the film was ‘made especially for front-line soldiers of the Russian army’. It contains no scenes of military action, but shows soldiers at the Front celebrating Christmas – being brought presents, receiving guests, reminiscing about their ordinary life. This film has survived and is accessible on the Internet: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BlWrdMMg2Wk

Napoleon Inside Out

In the very unusual film Napoleon Inside Out (Napoleon naiznanku), produced by the Aleksandr Drankov company in 1914, mid-1910s society is depicted as a large zoo: roles in the film are played by trained animals.

Libretto:

Life in a small German border town passes quietly and peacefully. The peaceable inhabitants each go about their own business: two companions – German beer- brewers (puffed up turkeys) cannot divide their profits among themselves, get into an argument and finally begin to fight; lovers flirt (dogs lick each other); a wife makes a jealous scene for her husband (monkeys); young German students argue about politics and end up fighting (cats), and over all this the bright summer sun shines and the blue sky stretches its immense, enormous dome. Everything is quiet and cloudless. But suddenly… clouds gather somewhere in the distance, a little “Napoleon Inside Out”, who has got it into his head to reincarnate Napoleon the Great and to subjugate – no more no less than! – the entire world, is discussing his plan of war with those close to him and attempting to arouse a mood of militancy in his good German people (ducks, geese, dogs, pigs). Thanks to his intrigues European diplomats (foxes), who had been attempting to persuade each other of their utterly peaceful intentions, begin to snap and grumble threateningly. Their grumbling finds an echo in other countries – in Turkey a struggle flares up between parties (dogs) and it gradually mutates from deploying parliamentary methods to primitive domestic ones and ends in a fight. The mood of militancy aroused by “Napoleon Inside Out” creates a series of misunderstandings in the little border town. Young representatives of the German military (piglets) begin to behave provocatively with the local inhabitants – in full sight of everyone they peer unceremoniously through a crack in the wall of the women’s bath-house and so on. A local inhabitant (a monkey), indignant at their actions, takes them out on a boat-trip and drowns them as a punishment for their impudence. A German professor (a monkey), sent specially by “Napoleon Inside Out”, conducts an inspection of the picture gallery and destroys valuable works of art on the grounds that the German genius does not need “alien” art.

But by now the town is besieged by the enemy. The inhabitants (various birds and animals) are alarmed. They send an envoy (a poodle) to the enemy but meanwhile an enemy spy (a fox) has managed to get into the town and set fire to it. Firemen rush to put out the fire. The inhabitants hastily abandon the town. The pointsman (a monkey) gives priority to a train full of departing citizens. On a bridge it comes up against an enemy train. There is a crash. At the scene of the crash there are fragments of the train and the bodies of those who have perished… But somewhere far away at the same time the German HQ (a herd of pigs) waits pensively for news of victory, but instead soon hears the victorious Gallic cockerel announce the final annihilation of the German armoured fist and the dawn of eternal peace among nations.

‘Novye lenty (New pictures)’, Sine-Fono, 1914, 4-5, pp. 58-59

A series of films about “Vova”

And yet the most famous military comedies are a series of films about “Vova”, a student from an aristocratic family who goes to war – Vova Adapts (Vova prisposobilsia, 1916), Vova at War (Vova na voine, 1916), Vova on Leave (Vova v otpusku, 1916). Information also exists about a fourth film in the series which was not released, Vova the Revolutionary (Vova-revoliutsioner, 1917). The source for this series of films was an extremely successful play by Evstignei Mirovich, its success attested, for example, by the reviewers in the journals Proektor (Projector) and Obozrenie teatrov (Theatre Review).

Libretto of the first film about Vova, Vova Adapts:

A farce by А. Mirovich [Evstignei Mirovich is erroneously presented as A. Mirovich. – A.S.]. In the role of Vova an actor from the Saburov Theatre, Aleksandr Verner. The wealthy aristocratic student Vova, Baron von Strick, spent his time merrily and it seemed as if nothing could destroy the serene existence of the frivolous youth. But then students were called up and Vova spends his last evening with his friends. The young man did not go to any privileged training institute, did not want to resort to patronage, he decided to “adapt” to the conditions of military life and to be a simple soldier. And from a wealthy, aristocratic student Vova quickly turned into an entertaining soldier who amused his comrades and his superiors with his sincere desire to “adapt”, thus causing not a little anguish to his mother, a high society lady.

‘Novye lenty (New pictures)’, Sine-Fono, 1916, 9-10, p. 104

It was the opinion of many reviewers that the play was better than the film. The Theatre Review noted the long-windedness of the film. “The screen version includes invented scenes which are only alluded to in the play and it is these explanatory details which damage the general impression and dilute the genuine humour” (Obozrenie teatrov, 1916, 3119, 2 June). The reviewer in Projector wrote about the excessively caricatural acting of Aleksandr Verner, “who plays Vova more as some reckless, fast-living young man than as a mother’s boy from high society, pampered and arrogant, as the play’s plot indicates” (Proektor, 1916, 6, p. 12). But the critics of the Theatre Gazette were of a different opinion: “This merry farce works perhaps even better on screen; Vova is depicted in various situations and circumstances, which was not possible within the narrow confines of a two-act play” (Teatral´naia gazeta, 1916, 11, p. 17). The public liked the screen Vova: films about him were released one after the other and there is information about a further film, Vova the Revolutionary. In his memoirs Verner had this to say about the film’s popularity: “It’s amazing that this comedy, which makes evil fun of all these rotten aristocrats, and of their ostentatious, rickety “patriotism”, invariably aroused the loud and sincere laughter of those very counts and barons who evidently did not want to admit that they were so worthless and repulsive. The play was even performed at the Tsarist Court and won approval in “the highest circles”, and it was soon followed by sequels” (State Central Film Museum (GTsMK), f. 3, op. 2, ed. khr. 30, l. 8).

The image of Vova remained in the culture even in the 1920s. The commentators to the complete thirteen-volume edition of the works of Vladimir Maiakovskii, I.S. Eventov and Iu.L. Prokushev, point out that it was reflected in Maiakovskii’s epic poem Vladimir Il´ich Lenin (1924):

Imperialism

in all its nakedness –

with its belly hanging out,

its false teeth,

and a sea of blood

up to its knees –

gobbles up countries,

raising its bayonets.

Around it

are its toadies –

patriots –

the Vovas have adapted

they write,

after washing their traitorous hands:

- Worker,

fight on

to the last drop of blood!

V.V. Maiakovskii, ‘Vladimir Il´ich Lenin’, in Polnoe sobranie sochinenii v 13 tomakh, volume 6, Moscow, GIKhL, 1957, p. 271.

Have you spotted a typo?

Highlight it, click Ctrl+Enter and send us a message. Thank you for your help!

To be used only for spelling or punctuation mistakes.