Ready for Takeoff: Digital Humanities School Probes a Scholarly Frontier that Lies Beyond

‘Digital Humanities… is an attempt to model a complex idea in humanities scholarship using methods similar to those that were used to construct the first aircrafts: they are nice-looking, but highly impractical devices that often tend to break down.’ This is a definition put forward by Elijah Meeks, a Data Visualization Engineer at Apple, formerly employed with Stanford. The author of the ORBIS Map, he is one of the most prominent figures to have pioneered the field of DH.

Digital Humanities scholars launch a project

Held by the HSE Centre for Digital Humanities, the annual Moscow-Tartu School is something like a venue for aircraft enthusiasts at the dawn of aviation (such as those frequented by Sergei Korolev at the beginning of the 20th century). Once a year, eager practitioners gather in Voronovo—and, prior to that, Yasnaya Polyana—to model texts and other objects of inquiry in the humanities by using digital methods. In other words, they build intellectual ‘aircrafts’ that no previous scholars have attempted to construct.

Straight Talk about Digital Humanities

This year’s school was inaugurated by a lecture on the frustrations of Digital Humanities. DH-Centre Head Anastasiya Bonch-Osmolovskaya gave some ‘straight talk about an uncomfortable subject: why the Digital Humanities are so annoying and how to prevent losing your self-control’.

It is indeed easy to start feeling dejected if you have been building a plane for a number of years only to keep discovering more and more ‘laws of gravity’. It is this feeling of dejection that Anastasiya Bonch-Osmolovskaya focused on in her lecture. She spoke about the moments when it becomes clear that digital technology does not necessarily guarantee better reliability, comprehensiveness, or even speed. Let alone the depth of analysis, as primitive things in fiction that can be calculated on the computer still cause sneers on the faces of non-digital humanities scholars.

What can be done? Bonch-Osmolovskaya suggests roughly the following: have patience and try to carry out deeper research by applying more complex and elaborate methods. Use word frequency and noun categories to detect elements of the plot. Use social networks of characters to produce multifaceted and multidimensional models of their activities and interaction. At the same time, we should not forget about our humanitarian roots: there will be much more sense in Digital Humanities if the computer does something comparable to what Vladimir Propp did with fairy tales, rather than just generating graphs of the word ‘war’ in Tolstoy’s War and Peace.

A video of Anastasiya Bonch-Osmolovskaya’s presentation

Practice: from Vector Semantics to GIS

Having overcome some of their dejection (partly thanks to the lunch break—the centre in Voronovo feeds its guests well), the participants attended workshops. This is the least ‘magical’ part of the school programme, as it is more technical: participants attend two classes dedicated to a specific method or technology. This year, participants could choose among tutorials on semantic vector models, stylometry, geoinformational systems, topical modelling, and a combined workshop ‘Digital Approaches to Russian Literature’.

Workshops are useful in that they allow you to gain hands-on experience, analyze data, get a computer to do something, and see the results. This is as perfect an antidote to DH-frustration as chocolate is to dementors. In their feedback on the school, participants lamented not having been able to attend several workshops at a time and expressed support for expanding the hands-on programme of the school.

This may be because I am a newcomer to the field, but I’d like to see more workshops that we could attend on the first day. They provide a good toolkit there. Many of us wanted (but didn’t have the opportunity) to attend two or three of the workshops.

Julia Brukhanova, participant

Participant conference

On the night of the first day, everyone gathered in the auditorium to hear presentations by participants who were brave enough to present their own research findings. The audience discussed the advantages and disadvantages of quantitative methods in analyzing literature and fiction (from classic plays and novels to fan fiction). They discussed computer vision in movies. They debated the extent to which digital analysis is ‘omnipotent’, whether it can sustain research devoid of particular aims and objectives (that is, charlatanism), and what the meaning is behind the frequency of the word ‘poet’ in Alexander Pushkin’s poems.

Presentation on quantitative methods in film studies by participant Maria Knysheva

The key advantage of such conferences in Voronovo seems to be an opportunity to receive useful feedback and connect with scholars who are eager to give a hand with coding, mapping, and even writing an article—anything to make the research possible. Such venues give birth to research teams and laboratories just because people felt like getting together to study fanfics.

‘Think Hack’ with a Chinese Bestiary Added in

The main component of the programme began on the morning of the second day, when tutorials were presented. Apart from food, tutorials are the main ingredient of the Moscow-Tartu School on Digital Humanities—its ‘killer feature’. A tutorial is somewhere between a think tank and a hackathon. The organizers of each tutorial bring interesting social and human science data, and the participants of each team analyze these data using both digital and other analogous methods. The following six tutorials were held this year:

-

What Does a Virtual Home Consist of? Menu categories of early Russian website home pages

-

The Moscow and Leningrad Cinema Market of the 1920s: analyzing statistics of cinemas in the formative years of the Soviet film industry

-

Further Diary Reading: analysis of the past life’s tones as part of the Past Years project

-

Anatomy of Life: developing a data exchange standard in prosopographic research

-

Liturgical Texts: implied and explicit parallels—analyzing Russian Orthodox Church’ liturgical texts in different languages (Church Slavonic, French, Afrikaans, and contemporary Russian)

-

Movies for Everyone: comparative analysis of pose recognition and facial key point detection in movies and life by computer vision methods

During the introduction, the teams spoke about the current status and ultimate aims of their projects: what data has already been prepared, what has yet to be received, and what the teams want to calculate, model, measure, and understand. See, for example, the introduction of the tutorial on liturgical texts by Fr. Pantelaymon, father-superior of the Troitskii Danilov Monastery in Pereslavl:

And here is a brief excerpt of the introduction of the ‘Movies for Everyone’ team (with leader and author Ildar Belialov, expert in machinery, Director of the Deep Learning Programme at the Summer School). Thanks to Ildar and his team, the school has gone beyond text (hypertext) research—this is the first time we have had a real computer vision.

After lunch (we’ve already mentioned that food is one of the main attractions of Voronovo, right?), the teams went to different rooms and began to brainstorm, come up with and test hypotheses, and dig deep into data. This group tutorial work was interspersed by lectures from visiting experts:

- Roman Leybov (Tartu University) and Boris Orekhov (HSE University) talked about research on the topic of Crimea on the major Russian amateur poetry website, Stihi.ru. Hundreds of thousands of authors publish their poems on Stihi.ru (there are as many as 47 million poems there. Yes, you read that right: millions). Unlike blogs and social networks, they can hardly be suspected of being overwhelmingly biased, so Stihi.ru is an interesting site not only for people keen on amateur poetry, but for researchers of public attitudes and opinions. The lecture presented an analysis of amateur poets’ attitudes to Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea.

- Mariana Zorkina (University of Zurich) presented her study of the bestiary in poetry written the Tang Dynasty. Poems of that time feature tigers, unicorns, lions, camels, hares, and other animals—real or imaginary—that lived in China or are known to Chinese people only by legends. The contexts in which animals were mentioned and their peculiar ‘semantic halos’ were examined with the aid of vector models (word2vec) and topical modelling. In particular, researchers determined which animals were closer to which religion (the lion is close to Buddhism, no kidding), which animals were significant in the context of international relations, and which smelled worse. For studying the co-occurrence of animals, network analysis was used.

- Andrey Kutuzov (University of Oslo/RusVectōrēs) lectured on why the world is shifting to the use of context-based vector-semantic models (ELMo, BERT), while classic word2vec has fallen out of vogue. Context-based models are trained to generate vectors of each word based on context.

When not at lectures, school participants got more and more involved in the workshop-like atmosphere of the tutorials. The teams stayed up late in their classrooms, working on their laptops occupying all the sofas, and discussing tasks and output in smoking areas, in the dining hall, and in the specially designated Lobby and Foyer.

The Results of Their Attempts to Fly

Traditionally, the School’s final event is reminiscent of a hackathon final round. On the last day, participants, engrossed in coding, but spurred by the deadline and imminent arrival of the buses back to Moscow, were hastily wheeling out their presentations. Some of them were still coding right up until the moment they had to take the stage (or even still when they were on stage).

Final Presentations

The participants of the Russian Orthodox Church Liturgical Texts tutorial began by discussing the technology they used. To align the texts in Afrikaans, French, Church Slavonic, and Russian, they needed a large number of NLP-tools: lemmatizers, stemmers, aligners, etc. The first version of the parallel corpus allowed the participants to make some non-trivial observations. For instance, they were able to trace variations of the translation of the name Mesopotamia (in French and Afrikaans, it is called ‘Paddan Aram’ as it is in in Hebrew, while in Russian and Church Slavonic it is called ‘Mesopotamia’ as it is in the Greek Bible).

Final presentation of the Liturgical Texts team at the 4th Moscow-Tartu School

The participants of the ‘Further Diary Reading’ tutorial worked on the texts of the personal diaries of the Past Years under the guidance of HSE HD Centre Fellows Anastasiya Bonch-Osmolovskaya and Boris Orekhov. After checking the dataset and correcting some errors (e.g., one of the women appeared to have been keeping her diary since she was three), everybody was divided into three teams. The Data Scientists (Data Satanists) were in charge of initial processing and visualizing data; the ТМsts (topical modulators) were responsible for topical modelling; while the others performed lexical and semantic analysis, working both on their own selection and men and women’s notes separately. They finally managed to produce beautiful graphs and make conclusions on the way the diaries reflected the Great Terror and on the range of men’s and women’s emotional experiences.

The ‘Movies for Everyone’ tutorial by Ildar Belialov ushered in an era of computer vision at the Moscow-Tartu Schools. The Participants of this team were looking for a metric that would measure expressivity of actors in videos. This metric turned out to be arm angle changes and the changing distances from a subject’s brow to his or her eye. Using the metric, we can analyze entire periods of the cinematographic development without having to watch every movie (thanks to distant viewing, similar to distant reading). Not only did the tutorial yield some promising results, it also offered its participants a chance to apply for the ADHO 2020 conference.

While ‘Movies for Everyone’ constituted an entirely new page in the history of Moscow-Tartu Schools, the ‘Virtual Home’ tutorial was a project by a veteran team and seasoned summer school participants from the Internet and Society Fan Club. The participants dealt with internet archeology, looking into the structure of early Russian websites and web-ecosystems, in particular, those of Tomsk University, the so-called ToNet.

Final presentation of the ‘Virtual Home’ team at the 4th Moscow-Tartu School

ToNet used to be an independent segment of the Russian Internet, providing its services to Tomsk and the Tomsk Oblast. From about 1998 to 2008, ToNet developed in isolation from the rest of Russian Internet (RuNet) due to peculiarities of the local Tomsk providers. Within the city, its traffic was practically free of charge, and the speed was very high (thanks to fiber optics); while it cost a lot to go beyond the ToNet limits (one could pay as much as an average monthly salary for a hundred megabits). This resulted in a peculiar digital ecosystem within one city. ToNet became a unique cultural phenomenon of the time.

Having previously collected and processed a set of initial codes of archived ToNet home pages, the tutorial participants studied the composition of the menus: Guest Book, News, Links, Archive, etc. The researchers also searched for traces of specific web tools in the initial code. Although some of the ToNet web-masters appeared to have written their websites manually in html, the majority of the creators used standard frameworks such as Frontpage or HomeSite. The most popular system turned out to be the Tomsk local system SIPS Stack rather than traditional Microsoft or Macromedia/Adobe products. The team plans to look for the borders of ToNet web and ToNet infrastructure and focus on the ‘background’ data of the historical volume.

The ‘Anatomy of Life’ team developed a convenient and user-friendly digital format of biographical data representation (for those who want more than Wkikdata with RDF). While mastering XML and TEI tools, the participants learned how to convert unstructured biographies (specifically, writers’ biographies) into a form eligible for machines.

Final presentation of the ‘Anatomy of Life’ team at the 4th Moscow-Tartu School

The tutorial resulted in the first draft structure of biographical data. If stored in this format, data will enable researchers to answer questions such as ‘Whose first book was published earlier? Did the writers visit the same city? Who lived the shortest life? Who wrote the work with the longest title? Which writers held high military ranks? Who had a university degree?’

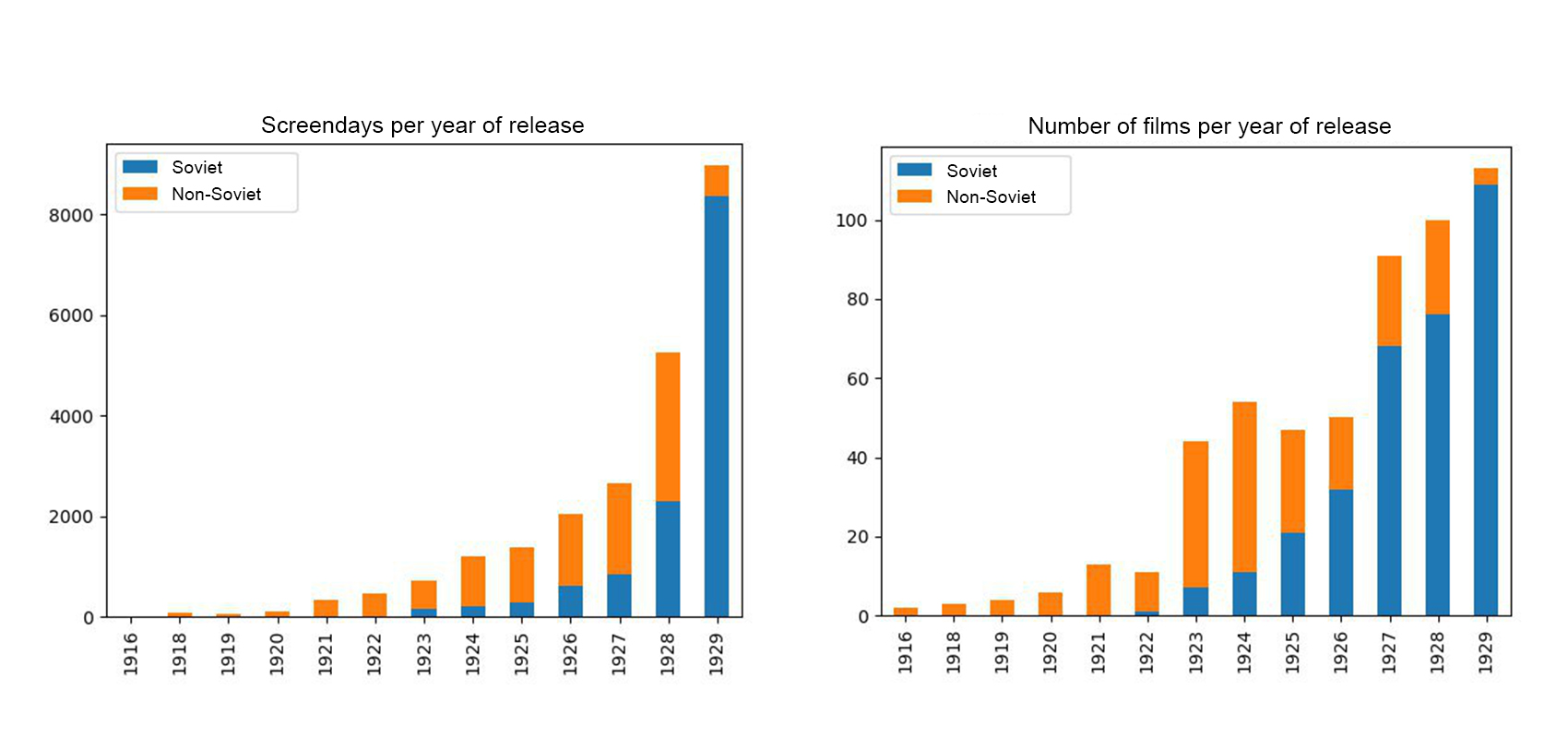

‘Moscow and Leningrad Cinema Market’, the sixth tutorial of the Voronovo School, looked into tastes of the early Soviet film viewer. The authors of the tutorial brought data that allowed participants to see when foreign movies were substituted by the Soviet films:

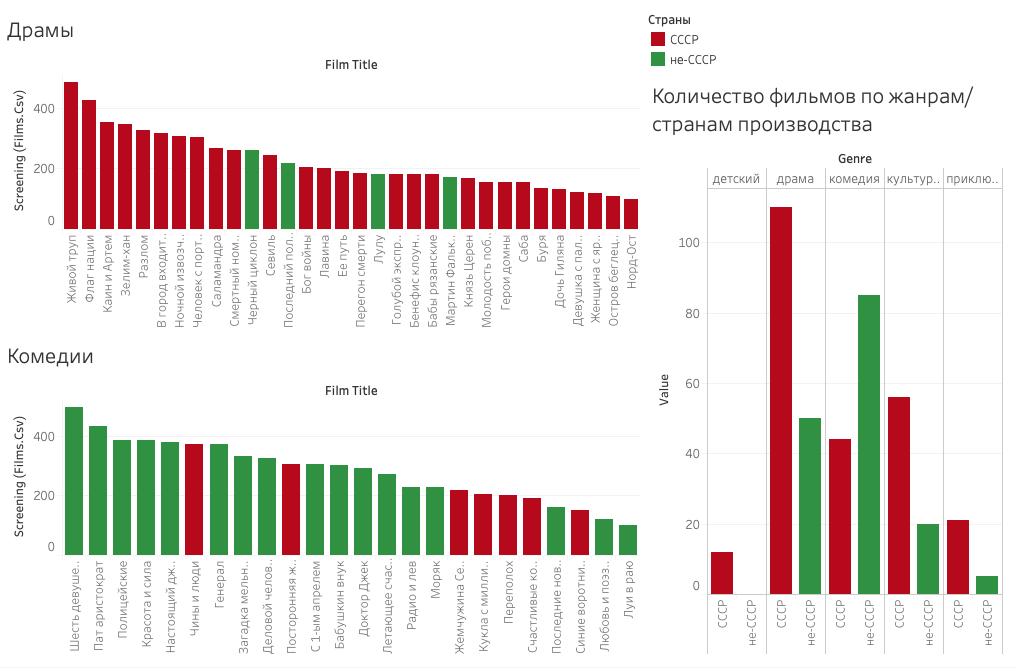

… how this happened (or did not happen) in different film genres:

… as well as what themes film screenings featured on what day of the week:

.png)

..and many other things.

So what?

It is always quite difficult to take stock of something. Let’s hope that the 4th Moscow-Tartu School has become another mainstay of the Russian and global Digital Humanities sphere. Its 90 participants from several countries and cities will hardly forget the meme about charlatanism (see Straight Talk about Digital Humanities’ above).

On a slightly more serious note, the variety of events held—lectures, conferences, workshops and tutorials—once again proves that the Digital Humanities stand only at the thresholds to the Schools of Science, Sorcery, and Interdisciplinary Areas. We still have to experience a plethora of disappointments, reconsiderations, and dead-end solutions. However, everlasting reflection and going ‘per aspera ad astra’ (through hardships to the stars) is the sense of existence. Although the Digital Humanities still have not yielded any flying machines, there are already hints of a vast digital humanities cosmos yet to be explored.

Feedback on the School

It was an engrossing discussion that engaged almost all participants, irrespective of their background. I was a bit worried at first that my complete lack of programming skills would greatly hinder me at the event, but fortunately other skills were needed too. Besides, the leader managed to create a comfortable atmosphere; he didn’t sort us out into those who ‘can’ and those who ‘cannot’. Up until the very last moment, we thought we would have no result to present, but the ‘measure twice and cut once’ principle worked well, and we were able to make a nice presentation after some thorough discussions.

Yelena, participant

I bow down to the organizers of the school—there was absolutely nothing to complain about with regard to both the technical and logistical aspects. It is good that the lectures were recorded. And the food was very good.

Fr. Pantelaymon (Korolyev), Tutorial Leader

Amazing! This is such a cool event: the programme, the participants, the merch, the food, the woods—it was just a blast! I would love to visit the next school as a volunteer.

Eugenia Zakovorotnaya, participant

I liked the programme. Although it was intense, we still had time for walks in the woods, which we also liked.

Maria Podryadchikova, participant

Everything was great! This was my first time at the school, and it was exciting. I went because I wanted to find out whether my research had any potential. The conference and the school helped me understand what methods I could use in my research. Now I see that there is a DH-community in Russian universities. :)

Pirozhok

My sincere thanks to the organizers and creators of the school for the wonderful atmosphere and the opportunity to work with interesting data, listen to lectures by talented speakers, ask questions, and receive well-structured insight in DH. It was a very inspiring and valuable event for the future development of this area at our university.I would like to thank Anastasia Alexandrovna for organizing and holding the tutorial, Daniil Andreevich for organizing the event and giving a very inspiring pep talk at the end, and to all the participants for such a tremendous feast of mind. Excellent accommodation, fresh air (sometimes), a forest, and peace and quiet all around. This exciting event is over, but it would be great if we could continue training and socializing, studying data and collaborating on some projects together. I wonder what a DH community venue for further work would be like.

Yelena Severina, participant